By all accounts, Charles F. Ritter was a family man. He had seven children, and when he was not working or attending Lodge meetings, he spent all of his time at home. Everyone agreed that he loved his family very much, and he seemed quite dependable at work. But in November of 1895, Ritter left his home, his job, and his club and was never seen again.

When the Tacony Trust Fund and Savings Company first opened its doors in 1892, Charles Ritter was hired straight away. He and his family lived in housing owned by the Trust Company, and he began working as a Paying Teller with an annual salary of $1,000. As his family grew, he continued to work at the Trust Company. By 1895, he was an Assistant Secretary and Paying Teller with a $1,200 annual salary. His oldest son was 16, and he and his wife had a new baby at home.

In the weeks leading up to his disappearance, however, his wife began to notice some changes in him. According to her, he appeared to be depressed. When she asked him to confide in her, he would only say that he was afraid the cash account at the bank would not balance properly, but he insisted that it would turn out alright in the end. She had no choice but to believe him, until on November 16th, 1895 he left her with only a letter of explanation.

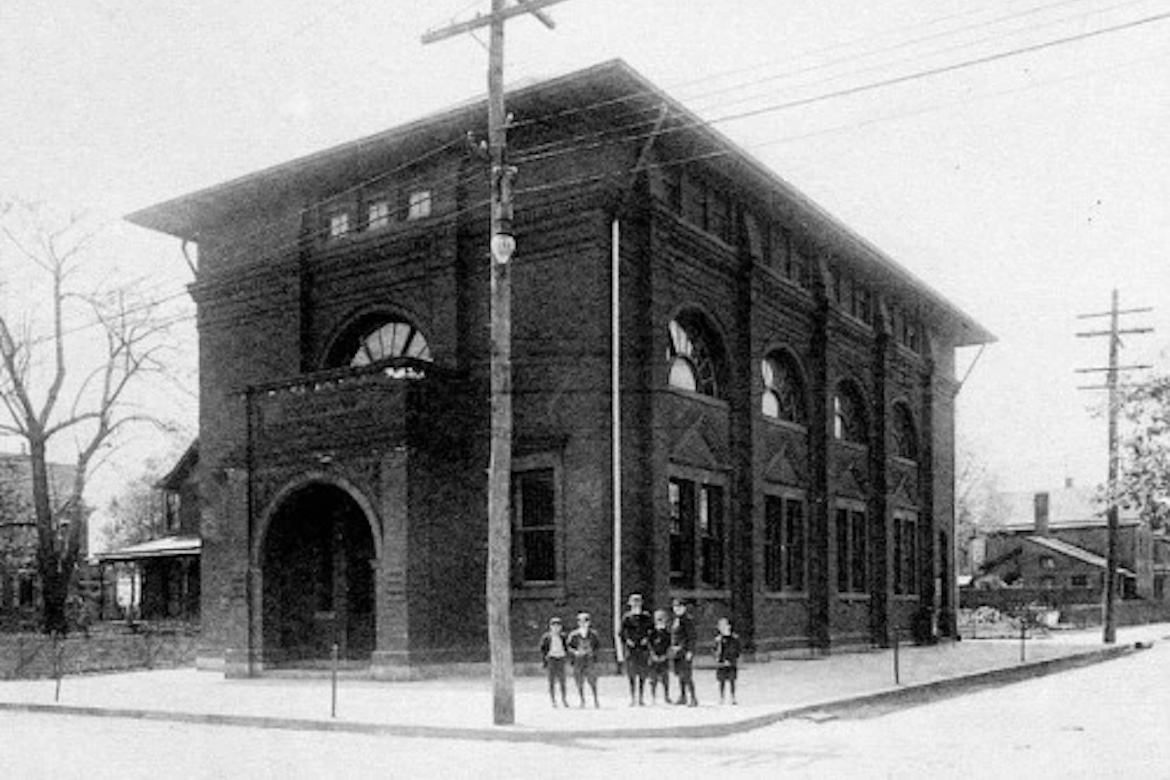

Saturday, November 16th was a day like any other for the Ritter family. That morning, Charles’ wife informed him that she was going into Philadelphia and would return in the afternoon. Charles went to work at the bank, located on the corner of Tulip and Longshore, and remained there until after Vice President Lewis R. Dick and the other tellers had gone home. At 6, he walked back to his house and told his oldest daughter that he would not be home in time for supper before leaving once more. The last credible sighting of Charles F. Ritter was on a train from Tacony to Philadelphia that left at 7:20 PM. A brakeman told police that Ritter got off at Penn Station, and the trail ended there.

Ritter’s wife returned home just after 9 that evening, and was surprised to hear that he had not come home for supper. When she went to their bedroom, she found an envelope addressed to her in his handwriting. The letter read:

“My Dear Wife– I well know what your suffering will be when you read this, but I am tired of the sight of books and everything relating to them, and I know you will forgive me for doing as I have done if you only knew all, but you will have enough to bear and I hope God will give you the strength and courage to keep up. Now try and be careful and tell the children to be good and kind to you, for your struggle through life will be a hard one without their support, and help from One adobe, who will be good to you in your hour of affliction. I would like to see you all once more, but the deed must be done, and I must not give way to my feelings. God be with you all is my last prayer.”

Fearing the worst, Mrs. Ritter immediately when to her nearest neighbor, William B. Snyder, who alerted the police and contacted Vice President of the Tacony Trust Fund, Lewis Dick. By this point, Mr. Dick had also received a letter from Ritter in which he confessed to misappropriating funds and told of his plan to run. The Vice President immediately called for an emergency meeting of bank officials. At the meeting, bank directors decided to seek the advice of Magistrate Thomas South, who lived nearby. At South’s advice, they charged Ritter with misappropriating funds and filed a warrant against him. Word was sent to the Captain of Detectives Miller, and the search initiated.

While police searched, bank officials began an investigation into Ritter’s accounts to find the discrepancies. Initially, they found nothing wrong. His cash account appeared well-balanced, he had not taken the $7,500 in cash that was at his desk, and the $200,000 in the safe was still intact. There were some who banked at the Trust Company that had taken their cash out when the news first broke, who returned it once reports came that everything appeared to be alright. Initially, it was speculated that he could not have taken more than $1500. But on November 22nd, the report was completed and it was determined just how much he had gotten away with.

According to bank officials, Ritter had spent his entire three year career at the bank systematically taking small amounts of cash to a total of $1841.90. As search efforts continued, the Trust Company issued an official statement on Monday, November 25th and declared Ritter’s teller position vacant. Newspapers reported that his wife was greatly distressed and believed he had committed suicide. Following the official report from the bank, nothing on Charles F. Ritter or the family he left behind was reported again.

Sources:

“Paying Teller’s Strange Flight,” The Philadelphia Times p.1, Nov 19, 1895.

“A Bank Teller Absconds,” The York Daily p. 1, Nov 19, 1895.

“No News of Ritter,” The Philadelphia Times p. 1, Nov 21, 1895.

“Ritter Had a System,” Wilkes-Barre Semi-Weekly Record, p. 2, Nov 22, 1895.

“Ritter’s Shortage Not Large,” The Philadelphia Times p. 7, Nov 23, 1895.